“Lent is a relic from the Dark Ages. It is a shadow projected from the ages of gloom that falls athwart the sunshine of our modern life and happiness. As the Matterhorn that lifts its snow-crowned summit high into the skies of Switzerland, intercepts the slanting rays of the setting sun and brings premature darkness to the little village nestling in the valley behind it, so Lent robs us of much of the brightness of social life and worldly amusement, casting prematurely across the noonday of our life the shadow of death and the hereafter. Its doctrine of mortification runs counter to the very grain of our human nature. It is a killjoy, an anachronism in our enlightened twentieth century. We want a religion of joy and gladness, not of gloom.”

Such is the cry that we hear about us on every side the cry of the epicurean, the cry of the cynic, the cry of the sophisticated, seeking through a thousand devious routes to find the Blue Bird of happiness. Is Lent really a barrier to our happiness? Is it the mere blind handing down of a custom from the hoary past, that has lost its purpose and its utility for our modern day? Let us face these questions frankly and fairly. For unless a person understands how the observance of Lent promotes his welfare and happiness he is not likely to enter into its spirit whole-heartedly.

Example of Christ

In the first place Lent is but the following of the example of Our Divine Saviour Himself. For, the Gospel tells us that immediately after His baptism in the Jordan and before beginning His public ministry, Christ went out into the desert and fasted forty days and forty nights. Through the lips of His precursor, St. John the Baptist, He said to the people: “Unless you do penance you shall likewise perish.” Unlike our modem generals who send their soldiers out into the front line trenches while they remain securely behind, Our Divine Master asks us to follow only where He Himself has led. For many centuries the Christian world followed the example of Our Saviour with a rigorousness which we today do not even remotely approximate. A few years ago I stood at the foot of Mt. Quarantana within sight of the Jordan, where the Saviour spent forty days of fast. I saw the sides of the Mountain studded with holes where anchorites had come to dwell and to follow literally the rigorous fast of the Saviour.

Until the ninth century but one meal a day was taken, and that at evening. During the Middle Ages not only the theaters but even the law courts were closed. War was forbidden under penalty of excommunication. Every activity that might distract the minds of the Christians from the consideration of the condition of their souls and the attainment of their eternal salvation was pro- hibited. It has only been in recent times that the severity of the Lenten fast has been so greatly mitigated that now we experience but little hardship in its observance.

Analysis of St. Paul

Catholics do not observe Lent, however, merely because Our Saviour fasted, but because of the reasons which lie behind His command — to do penance as the necessary condition for salvation. We do penance for a twofold purpose. First, to atone for our past sins and to satisfy the temporal punishment due for them. Secondly, to strengthen our wills so as to prevent our falling in the future.

When psychology will have written its final chapter on human nature, it will be found that it has given us no more penetrating revelation of its conflicting duality than that which St. Paul disclosed to the Romans when he said: “I see another law in my members fighting against the law of my mind, and captivating me in the law of sin that is in my members.” And to the Galatians he said : “For the flesh lusteth against the spirit, and the spirit against the flesh; for these are contrary one to another so that you do not the things that you would.” Because of this conflicting duality that lay at the very heart of his nature, he found himself yielding to the thralldom of the senses and to the imperious tyranny of flesh against the voice of reason and conscience so that he was compelled to explain : “The good which I will, I do not; but the evil which I will not, that I do.”

How aptly do these words of St. Paul reflect the experience of all mankind. Because of this duality in our nature we And a Dr. Jekyll and a Mr. Hyde, a saint and a demon struggling for the mastery in each of us. In the last analysis it will be found that the whole purpose of all the exercises of the spiritual life is to emancipate the will from the tyranny of the flesh, to make it the ready servant of the reason and the conscience of man.

In order to secure such mastery, self-denial and self-discipline are necessary. The appetite which is always pampered, petted and indulged, becomes imperious and domineering. By denying oneself at times pleasures that are lawful we strengthen the muscles of the will, so that it will be more capable of resisting pleasures which are unlawful. That is why in Lent we are asked to give up some pleasures and amusements which are lawful in themselves. We thereby fortify the enthronement of our conscience and our intellect over our appetites and cravings. Then when the temptation comes we shall be able to stand unshaken.

Promotes Happiness

Strength of will which comes through self-denial and discipline is necessary to success in every line of endeavor — in literature, in science, in art, in commerce, in athletics. Look at the athletes who are training day after day on the cinder track. See those muscles of theirs,at first soft and flabby, change under the dint of daily discipline until they become as sinews of iron. So it is with the Christian, whose will at first soft and flabby gradually becomes like iron under the lash of daily discipline during Lent. This strength of will devel-

oped by spiritual exercises carries over into every department of life — making for success in scholarship, in athletics, in business, in life.

Not only does it make for success, but it makes for that subjective correlate of success — happiness and peace of mind. True happiness is found not in the enslavement of the will to the passions, but in the enthronement of the conscience and the will over the appetites and the instincts of man. There is found that deeper and truer happiness which is not dependent upon external circumstances, but is found within — in the kingdom of the mind. Your entering generously into the spirit of Lent will have a far reaching influence not only upon the success of all your manifold activities, but also upon your happiness and peace of mind.

Sometime ago the students at the University of Illinois honored at a public mass meeting the young man who carried the colors of Illinois to victory at the Olympic games at

Amsterdam by winning the welterweight wrestling championship of the world. After congratulating him upon his great achievement, I asked him how long he had trained for the contest. “Father,” he said, “scarcely a day has passed in the last seven years that I haven’t gone through some special exercise designed to prepare me for that encounter.” No wonder that he was as hard as iron and steel and able to withstand the assaults of the best wrestlers among all the nations of the world. If men toil and discipline themselves through rigorous self-denial to win a race for an earthly prize, how much greater should be our zeal and earnestness in seeking to win the race of life that leads to a crown of imperishable glory!

Christ’s Self-Control

If one will study with care the character of Our Divine Saviour as portrayed in the Gospel stories, he will find it adorned in an eminent degree with all the qualities which have distinguished the illustrious heroes of the world. Wisdom, power, mercy and love shine forth luminously from His sublime personality. But as one studies that complex character at greater length and secures a more penetrating insight into it, he gradually becomes conscious that there is some subtle quality there, blending all these into a harmonious whole, which is lacking in the character of the great heroes of the world. There is no jar, no jolt, none of the strange inconsistencies that glare out at us from the lives of the secular heroes.

That quality is the Saviour’s perfect self-mastery, self-control. Never for an instant in all the scenes of the Master’s earthly life is there an incident wherein a rash, hasty, head- strong action mars the even tenor and the surpassing beauty of the Saviour’s unfailing equanimity and perfect self-control. Washington’s greatness bears ever the tarnish of his profanity and ill temper. Napoleon’s glory is dimmed by his uncontrolled concupiscence. But when on trial for His life before the court of Caiphas, when buffeted and spat upon by His executioners, even when stripped of His garments and nailed to the Cross, the Master shows no sign of anger or vindictiveness. Never for a moment does He lose that marvelous mastery of Himself.

That is one of the reasons why the name of Jesus stands out among all the names in human history — the solitary example of perfect self-control. As Richter has said: “The purest among the strong, and the strongest among the pure, Jesus lifted with His wounded hands empires from their hinges and changed the stream of centuries.” He taught man the greatest of all arts — the art of self-control.

“Self-knowledge, self-reverence, self-control In these alone lie sovereign power Who conquers self, rules others Aye, is lord and ruler of the universe.”

Essential for Success

The person who would master the rudiments of the spiritual life must learn the lesson of self-discipline. It is one of the most essential elements for success in the earthly and spirit- ual warfare which we wage. The paths of life are strewn with the wrecks of men and women conquering others, mastering the arts, unlocking the secrets that lay hidden for countless centuries in the unfathomed bosom of the earth, only to fall victims to their own lusts, perishing in their own unconquered wilderness.

To me there is something tragically moving in the spectacle of Alexander the Great, subjugating Greece, conquering imperial Rome, extending his little kingdom of Macedonia over the known world, until he found himself in distant Ecbatana in Media, Asia, sitting astride his steed and weeping because there were no more worlds to conquer. Within a week Alexander the Great, conqueror of the world, making the earth tremble as his mighty battalion swept across Europe and Asia, lay dead in his tent, a victim to his own concupiscence — his un- bridled passion for drink. Instead of sighing for new worlds to conquer, if he had but eyes to see, he would have perceived within himself a kingdom which stretched out as a huge jungle, untamed and unexplored. Alexander the Great will remain for all times as the classic example of the man who was able to conquer all the world, except himself — literally murdered at the very zenith of his greatness by his own untamed passions.

We need not go back to ancient Greece or Rome or Ecbatana, however, to witness the tragic wrecks of uncontrolled passions. Our insane asylums, our homes for wayward boys and girls, scream out at us their message of the frightful retribution meted out to those who allow their lust to subjugate their reason and their conscience. In the very bosom of our society are countless men and women in the untamed wilderness of whose hearts there surge unchecked, wild, primaeval passions, pulling them down slowly but surely to the level of beasts, and murdering every- thing in their nature that is God-like and divine. The ceaseless gnawings of remorse, the sapping of their manhood and virility by terrible diseases — these are the forebodings of the far greater punishments that await with inexorable justice the transgressors of the Divine law in eternity.

A Dying Wreck

One evening some time ago I was called to the beside of a stranger, dying in one of the rooming houses for transients in the city. He had gone through all the stages of delirium tremens, and was a complete wreck. The doctor said that he had gone on one spree too many. For this one had caused complications, a ruptured blood-vessel, and his end was a matter of hours. Though only in middle age his hair was streaked with gray, and his face was heavily lined. Worry and dissipation were stamped unmistakably upon the scarred countenance. Heartbroken, he told me his story. Possessing a good education, he had risen to a high position with a railroad, when he contracted the habit of drunkenness. Losing his job after a prolonged fit of intoxication, he was ashamed to face his wife and children. He went from bad to worse, finally becoming an outcast among the barrel houses in a large city.

After I heard his confession, he broke into tears, and his whole frame shook with sobbing, as he cried. “Father, I would have given anything in the world to have freed myself from this terrible vice of drink. It has brought shame upon my family whom I love more than anything in life. It has pulled me down into a living hell.” I shall never forget to my dying day the look of desolating anguish akin to despair in his wistful eyes, as he lay there sobbing as though his heart would break.

As I left that bare drab room, with its dying victim, and came down the creaking stairs of the dingy rooming house, the scene haunted my mind. While hurrying home through the darkness of that winter night, illumined only by the distant stars shining as God’s silent sentinels in the sky, I prayed that God might protect my students, my people, myself from a

tragedy such as I had left behind. For that is the fate which awaits the boy or girl, the man or woman who allows any passion to grow unchecked, until it transforms him from a saint into a demon incarnate — the terrible tragedy of the man who is murdered, not by the hand of the assassin, but by his own brutal passions, slowly strangled to death by his own self.

The whole world watched breathlessly a few years ago the frantic struggle of men to free a victim from the jaws of Sand Cave in the Kentucky hillsides. But they resisted all the assaults of men and machinery, and clung to their victim until life was extinct. So, any passion — intoxication, lust, anger, jealousy — that is allowed to go unchecked, develops into a monster that clings to its victim until it strangles him to a physical and spiritual death. Worse than the fall of a meteor from the sky is the fall of a young man or a woman from the beauty and sunshine of God’s grace into the foul swamp of uncontrolled vice. It is the most tragic note and the saddest that can be sounded in the whole gamut of human life.

The Remedy

What now is the remedy? Knowledge merely? “Quarry the granite rock,” says Cardinal Newman, “with razors or moor the vessel with a thread of silk; then you may hope with such keen and delicate instruments as human knowledge and human reason to contend against those giants, the passions and the pride of men.” Not knowledge alone, but will power is needed. Self control means strength of will applied to one’s own conduct. How can will power be developed? Our Divine Master has given us the answer when He said: “He that will be my disciple, let him deny Himself, take up his cross daily, and follow Me.” By daily discipline, daily self denial, such as Lent brings to us. In no other way under the hea-vens can there be developed will power and self-control.

The same conclusion was reached by an altogether different method of approach by one of the greatest of all psychologists, William James, when he said: “Keep the faculty of effort alive in you by a little gratuituous exercise every day.” Do something each day that is hard and more than is required in order that your faculty of effort, your will, may not become weak and atrophied through disuse. Thus strikingly does science reiterate and re-enforce this age old teaching of the Church.

Before the eyes of a world, sick unto death with luxury and self indulgence, the Church places during Lent the age old picture drawn by the Master Artist, Christ, of will power de- veloped through self discipline, of self-control achieved through acts of self-denial. Greater than Napoleon Bonaparte, than Julius Caesar, than Alexander the Great, the conqueror of the world, is the man who has learned through the instrument of a vigorous will to conquer himself. For self-control is the open sesame to success in this life and to eternal happiness in the next. All the after ages have but confirmed the wisdom of those words of an obscure Flemish monk, Thomas a Kempis, written in his monastic cell at Zwolle centuries ago: “He who best knows how to endure. . . is conqueror of himself and lord of the world, the friend of Christ and an heir of heaven.”

“And Unto Dust ”

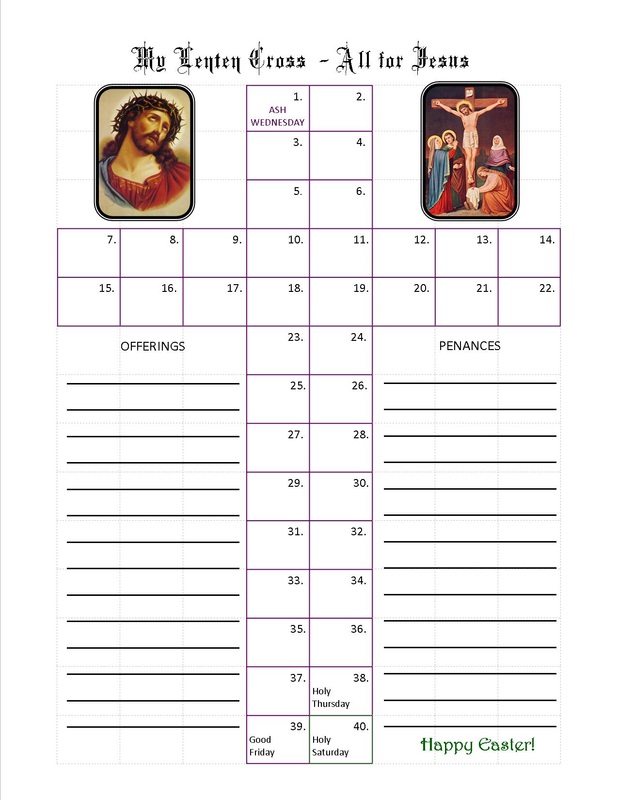

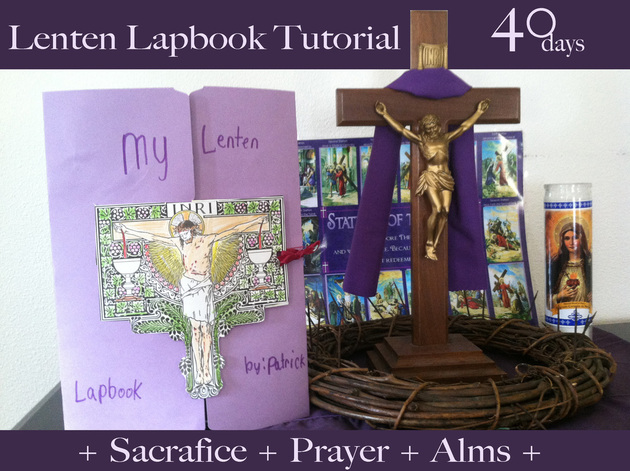

In addition to the great lesson of self-mastery. Lent brings home to mankind the fickleness of the world’s applause and its insufficiency to satisfy the hunger in the soul of man. On Ash Wednesday the Church seeks by a colorful and impressive ceremony to drive home to her children the transiency of this earthly life and the wisdom of seeking to attain the life eternal. The palms which were blessed on the previous Palm Sunday to remind us of the Saviour’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, when the multitudes waved them aloft shouting, “Hosanna to the Son of David”, and strewed them in profusion on the road over which he rode — these palms the Church burns to ashes. Then summoning her children to the altar railing she places these ashes on the brow of each in the form of a cross, while she whispers in the ear of each the words of warning: “Remember man thou art but dust, and unto dust thou shalt return.”

Why speak to youth in whose eager eyes there burn the fires of life, and on whose cheeks there rests the bloom of youthful vigor — why speak to them of dust and ashes, of death and the hereafter? Why lessen their zest for life and its pleasures? The Church thus speaks to them, not to lessen their zest for life, but to give them a sense of values. She shoves back the narrow horizon of youth, removes the veil from the senses, reveals the transient character of earthly things and points out the folly of seeking enduring happiness in that which is so ephemeral. The thought of death and the hereafter is salutary at times for old and young, for it prompts one to answer aright that supreme question which the Master addresses to each of us: “What doth it profit a man if he gain the whole world and suffer the loss of his own soul?”

The wholesome effect of a profound realization of the transiency of human life and human beauty is illustrated by an incident in the life of St. Francis Borgia. Francis was Duke of Gandia and Captain-General of Catalonia, and one of the most honored chevaliers at the Court of Spain. Isabella was known throughout Europe for her charm, her Spanish vivacity and for the striking beauty of her countenance. Often had Francis braved death while carrying the banner of Aragon and Castile into the thick of the battle, knowing that he would be rewarded with a word of praise from his beloved Queen. He found his greatest happiness in basking in the sunshine of her smile and drinking in with greedy eyes her charming loveliness.

A Last Look

In 1539 there fell to his lot the sad duty of escorting the remains of his beloved Queen to the royal burial grounds at Granada. In order to verify the body as that of Isabella, the coffin was uncovered. Eagerly Francis stepped forward to take one last lingering look at the beautiful countenance of his beloved Queen. He had no sooner done so than his face grew livid, his eyes wild with terror, as he shrank back. “No! No! Good God!” he cried, “it can’t be! It can’t be! Those eyes that face, that smile! They can’t have perished so utterly.” What was the sight that greeted his eyes? A face of wondrous beauty? No. A face hideous and ugly in its putrefaction, the loathsome prey of worms and maggots pulling it back to dush and ashes. “God grant,” cried Francis, “that I seek not to find my happiness henceforth in that flesh which perisheth so quickly, but only in that eternal Beauty which never knows decay.” Francis devoted his services thereafter to a heavenly King, seeking as a humble missionary to win souls for Christ.

From the most beautiful face in all Spain, for whose look of approval soldiers faced death with a smile, to a sight SO foul and loathsome as to fill the spectator with revulsion — what a change! Gaze at the most beautiful face you have ever seen, with eyes that speak like a rapturous symphony, with a smile that warms and endears, and in a few short years will you be able to overcome your loathing to gaze upon it when death has touched it with its finger of decay? “Remember man that thou art but dust, and unto dust thou shalt return.”

We need not go back, however, to the sixteenth century for striking instances of the transiency of earthly fame and the fickleness of human applause. On March 4, 1917, I stood in a crowd of 90,000 people before the Capitol in Washington, to watch the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson into the Presidency for his second term. His name was cheered on every side. A gigantic parade marched proudly before him in review. At the triumphant close of the World War when he sailed for France to dictate the terms of the Versailles Treaty of Peace, he had reached the eminence of world fame. His words about freedom and democracy and the autonomy of small nations had rekindled the hopes of all the oppressed nations of the earth. Unprecedented crowds greeted him at Paris with tumultuous cheering. The eyes of all the world were turned to him, as he stood on the pinnacle of human eminence as a new Moses, heaven-sent to lead the groping feet of the nations into the Promised Land of perpetual peace.

An Age Old Cry

A few years later I passed by a little home on H Street where lived a broken old man, unable to take more than a few steps with the aid of his cane. Broken in body, broken in mind, broken in heart, his League of Nations plan contemptuously rejected by the Senate, his opponent swept into office by the greatest landslide in history, the nations of Europe shaking their fists at him for deluding them with false hopes. What a pitiable spectacle ! As he gazed out of his window at night toward the Capitol ablaze with light, the scene of his brilliant feats, what memories must have stirred within him !

One night, it is narrated, Mrs. Wilson happened to step into the parlor. The room was dark. Seated in a chair near the front window with his face resting in his hands she perceived her husband. There was the sound of a few broken sobs. Placing her hand tenderly upon the bowed head, she asked softly: “Are you ill, dear?” The former president raised his head and

looked for a brief moment through tear-dimmed eyes toward the great shining Capitol that had resounded so often with his name. “No, not ill,” he said, “but I realize now as never before the fickleness of the plaudits of the multitude and the emptiness of the glory of this world.” As he sat there, broken in heart and alone, he tasted of that world weariness, that pang of the heart which caused Solomon in his old age to cry out: “Vanity of vanities, and all is vanity save in loving God and serving Him alone.”

It was echoed again by St. Augustine, when after running through the whole gamut of sensual indulgence in pagan Rome, he cried out: “Our hearts have been made for Thee, 0 God, and they shall never rest until they rest in Thee.” Such are the great eternal truths which Lent with its gospel of penance and self-denial, drives home to a world that is forever tempted to find its happiness over the more beguiling but mistaken paths of ease and self-indulgence.

Source: Penance and Self-Denial: Why? The Significance of Lenten Discipline for

Modern Life

Nihil Obstat: REV. T. E. DILLON, Censor Librorum

Imprimatur: +JOHN FRANCIS NOLL, D. D., Bishop of Fort Wayne

RSS Feed

RSS Feed