About 731 Gregory III. consecrated a chapel in St. Peter's church in honor of all the saints, from which time All Saints' Day has been kept in Rome, as now, on the first of November. From about the middle of the ninth century the feast came into general observance throughout the West. It ranks as a double of the first class, with an octave. That none of the elect might be omitted in the honor and veneration due them, this feast was established.

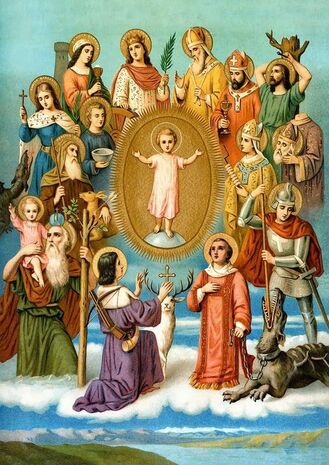

During the course of the year the Church offers for our contemplation the feast of one saint after another, but on this day she shows us the heavens opened and the countless multitude of the Elect from all nations, races and states of life. The Church celebrates her harvest feast on this day, showing herself the true Church that leads her children to eternal bliss. The true Christian, especially should feel on this day that he also is created for heaven. The sight of so many saints that were once human, like himself, enlivens the hope within him of reaching his eternal goal. Renewed courage and strength invigorates his heart. Penetrated with a lively faith in the Communion of Saints, he confidently calls upon the inhabitants of heaven for their powerful assistance.

By far the greater number of the Elect who have attained to the beatific vision are unknown to us. The Church honors only those as saints who either have suffered martyrdom, or whose sanctity has been indisputably confirmed. In former times bishops could declare a deceased person worthy of veneration, but now this right is reserved exclusively for the Pope. For this purpose the Church has established an exceedingly strict and deliberate process, which usually develops into three degrees,—that of Venerable, Blessed, and Saint. The first step of the process

is a formal inquiry as to whether the deceased practiced the virtues in an heroic degree. If this is

attested in the affirmative, then the deceased is declared venerable. The second degree is that of beatification. The person who is to be beatified must have practiced, in the heroic degree, chiefly, the three theological virtues,—Faith, Hope and Charity, and the four cardinal virtues,—Prudence, Justice, Fortitude and Temperance, with all that these suppose and involve. It must also be proved that four or at least two miracles have been wrought by the intercession of the person whose virtues are under debate; upon which the Pope declares him or her Blessed (Beatus), by virtue of which a limited public veneration is permitted. Canonization is the third and final degree in the recognition and estimation of the virtues of a servant of God, preparatory to his or her being elevated to the altars, and commended to the perpetual veneration and invocation of Christians throughout the Catholic Church. Before proceeding to canonization it must be proved that at least two miracles have been wrought through the intercession of the blessed person since the beatification. This proof is attended with the same formalities and surrounded by the same rigorous conditions as in the case of the miracles proved before beatification, whereupon the Pope declares, that the servant of God in question shall be inscribed on the register of the Saints. Though Rome from century to century, has established many miracles with the greatest judicial rigor and exactitude still the unbelieving world persist in denying, without further examination, the truth of these miracles; even going so far as to dispute their possibility. For the thoughtful Christian, these authenticated miracles are an indisputable proof that the Catholic Church is the sanctifying Ciurch of Christ. This proof is confirmed anew at every process of beatification or canonization.

Source: The Ecclesiastical Year for Schools and Institutions, Imprimatur 1903

RSS Feed

RSS Feed