FIRST POINT — The first excuse which we allege to exempt us from being saints is taken from the difficulties of sanctity in itself. We are wont to make of the saints a class of beings apart, a separate race, invested with some perfections inaccessible to the rest of Christians— a sublime exception in Christianity. Nothing is more false than this idea of sanctity. We employ it, however, to be free from the care of being holy. It is a strategy of nature, it is an error employed as a pretext to indulge in sloth. Unquestionably in the lives of the saints we meet with marvelous phenomena; God honors them with a familiarity which seems sometimes to separate them from us; He allows His love to fall on them in a manner which astonishes us, and they oftentimes respond to these gifts of God by an immolation of themselves which not only terrifies but astonishes us. These are, if you wish, recompenses, privileges, and marvels of their sanctity, but it is not their sanctity itself. The saints are what we Christians are, but they are better than we are. We are ordinary Christians, while the saints are eminent Christians; we are only soldiers, they are heroes. We must admit there is in sanctity a certain degree of perfection which only heroic souls attain. But we can be saints without rising so high, and the degree of virtue necessary to be a saint, in the ordinary sense of the word, has nothing which should terrify our courage. The command which I give you, said the Lord, is not beyond you. To observe it, it is not necessary to quit the world and to bury yourself in solitude; but it is within reach of every one, and its observance demands only the simplest requirements and the most ordinary works. How many saints are happy in heaven now who have done nothing on earth which has won for them the admiration of men! St. Augustine says that God is pleased to sanctify them in the obscurity of an ordinary life. Who is the servant in the Gospel whom we see rewarded? Is it not he who has been faithful in little things? Sanctity does not consist in doing extraordinary things. No; but it consists for all in fidelity to the duties of our state and in fulfilling them for God. There is nothing in that which is so difficult. The Christian complains of the difficulty of virtue. But how can he dare to do so with the example of the saints before him. Ah, if we had the choice between apostasy and the scaffold! — if it were necessary for us to sell our goods, abandon our friends, and condemn ourselves to solitude, what should we say? Then it would be indeed difficult to be saints! And yet we should do it, since the saints have. But what sanctity demands of us is much less than all that. It is a question of loving a God who is amiability itself, and not offending a God who is our Friend, our Father, and our Saviour. What is there in that that is above and beyond our strength? The worldling complains of the difficulty of virtue. How does he who serves the world dare to say this? Ah! if there is something difficult, it is to please the world, to bow to its caprices, to submit to all its requirements. But, O my God, Thou art good to all who serve Thee; amiable Master, Thou imposest precepts which are hard in appearance; but it is only a pretext, since Thou hast hidden sweetness under an apparent severity.

SECOND POINT — Excuses drawn from exterior difficulties. Virtue meets in the world with rude and countless obstacles, it is true; but our error is to conclude from that that sanctity is impracticable for us. And, after all, what are the obstacles? They are, first, the attractions of pleasures. But is not the world for saints as well as for us? Have they not found the world as deceitful in its caresses, as contagious in its examples, as false in its maxims, and as seductive in its pleasures? We complain of the tyranny which is exercised over our hearts, the love of worldly joys, the violence which we must do to hinder such amiable seduction; but, let us ask, when was victory achieved without combat? Do you think it cost no violence to Magdalen, to St. Augustine, to St. Jerome, and countless others, to break the bonds which bound them to iniquity and attached them to the world? What, then, hinders you from breaking these bonds as they have done? There is another danger which awaits us, and one that is remarkable for the countless shipwrecks it has occasioned; it is human respect. We could scarcely believe it were not our own eyes the witnesses of it. The fear of the world has become an obstacle to virtue. The Christian who wishes to serve his God must resolve to endure the railleries of libertines and the persecutions of the world; but the saints also met human respect face to face, and with what courage they were able to trample it under their feet! St. Paul was called to preach Christ crucified; but the cross is a folly in the eyes of the Gentiles, a scandal for the Jews, and he knows all this! Still it is nothing to him; Corinth, Rome, and Athens hear him preach the gospel of salvation freely. Let them despise him and calumniate him, let the world rise against him — he regards the judgments of men as nothing. Do you think that this contempt which was shown him cost St. Paul no effort? St. Augustine had also to overcome all that is terrible in human respect. What a sensation was created in the whole city of Milan when he broke away from all his past career ! What railleries on the part of countless young libertines who were formerly his best friends ! But St. Augustine triumphed over these obstacles; and it was not this only he had to conquer, but he had to break with the most ardent passions and the most inveterate habits. This was difficult. He himself depicts for us the violence of his combats, his long irresolutions, when, rolling himself on the earth, tearing his hair, he cursed his slavery without being able to free himself from its bondage. But at last, sustained by that grace which is never wanting to us, he broke his chains and by a generous effort arose above all his weaknesses. When shall you have the happiness to triumph over yourselves?

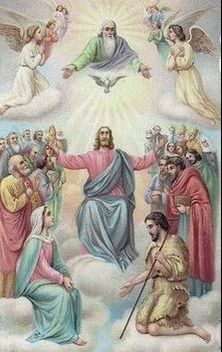

O my God, Thou who art in the highest heavens, surrounded by the immortal choirs of the elect, Thou who hast combated with so much courage. Thou beholdest my sloth and hearest my vain excuses. What must be Thy indignation! How shall I, one day, justify the monstrous contradiction which exists between my faith and my morals? What excuse shall I allege when Thou shalt point out to me saints of my own age and condition, who, in the midst of the same obstacles which arrest me, have remained faithful in the practice of all their duties? O my God, give me the strength to take them for my models. What happiness for me if, after having imitated their virtues, I may share their felicity and their glory!

Source: Short Instructions for Every Sunday of the Year and the Principal Feasts, Imprimatur 1897

RSS Feed

RSS Feed