By this time it had spread all over the City that Jesus of Nazareth had been taken and found guilty of death. Everyone was talking of Him. Some were surprised that a man who had spent his days in doing good should be so persecuted. Others said it had been found out that his wonderful works were done by the power of the devil. The priests had declared—and surely they should know best—that he was a dangerous man, who must be got out of the way, or he would bring ruin on the nation. And what were his feelings who had betrayed Him ? Perhaps Judas had persuaded himself that our Lord would escape unharmed from His enemies as He had often done before. At all events, the tidings that He had been condemned to death, and was being taken to Pilate that the sentence might be confirmed, filled him with unspeakable horror. What could he do to still the remorse of conscience that was torturing him? People said the priests were even now entering the Temple on their way to the Praetorium. He would hasten thither and give them hack the hateful pieces of silver which had brought him to this. A few minutes later the worshippers in the Temple were startled by seeing a wretched-looking man rush past them after the priests, who with their Prisoner were passing through the Courts.

"I have sinned" he cried, "in betraying innocent blood," and he held out both hands to them with the money. They looked at him with contempt.

"What is that to us?" they said; "look thou to it." The cruel words filled up the measure of his misery. He might have been saved yet had he thrown himself at the feet of Jesus, or gone away and wept like Peter. But though his heart was full of a fierce hatred of himself, there was no true contrition for his sin, no hope of forgiveness. He gave himself up to despair, and, casting down the money in the Temple, went into a lonely place near the Garden where he had betrayed his Master, and hanged himself.

The Governor had been told that the chief priests, followed by an immense crowd, were bringing Jesus of Nazareth to the Praetorium for judgment, and he prepared for one of his stormy interviews with the rulers of the people. Pilate disliked and despised the Jews, and was severe, often cruel in his dealing with them. But he had no prejudice against our Blessed Lord, of whom he had heard, not from public report alone, but from Claudia Procula, his wife. How she had come to hear of the young Teacher from Galilee, we are not told, but His gracious words and ways, the hatred of the rulers, the dangers that hedged Him round, had come to her knowledge, and her heart was drawn to Him. Whilst He was suffering in the Garden, Procula, too, was suffering in a dream on His account. Terrified now lest her husband should do anything against Him, she determined to follow the proceedings as far as possible from one of her apartments where she could see without being seen. Here, at the window, she stood watching with alarm the masses of excited people now approaching the Praetorium. Knowing that the chief priests were delivering up Jesus of Nazareth out of envy, Pilate was resolved to hear the cause himself and give the Prisoner a fair chance. He therefore gave orders that the priests should present themselves before his tribunal. But they would not defile themselves at this holy Paschal time by crossing the threshold of a Gentile, and the Governor had to go out and meet them in the great square in front of the Praetorium, called Lithostrotos, or the Pavement, from the coloured stones with which it was laid.

"What accusation do you bring against this Man?" he asked. They answered haughtily: "If He were not a malefactor we would not have delivered Him up to thee." And in loud, angry voices they began to accuse Him, saying:

"We have found this man perverting our nation, and forbidding to give tribute to Caesar, and saying that He is Christ the King." It was something new to Pilate to find this sudden zeal for Caesar, and he could not repress a sneering smile. But he was not going to condemn a man on no better evidence than their word, as they seemed to expect. Serious charges had been brought against Him, and Roman justice required that they should be seriously examined. He would see the Accused in private, and two of his guards were sent out to bring our Lord into the hall.

"Art Thou a King?" inquired the Governor. Jesus answered: "Thou sayest that I am a King. For this was I born and for this came I into the world . . but My Kingdom is not of this world."

It was as Pilate had been informed. The Man was no danger to Rome. He had always spoken peacefully to peaceful crowds. If His enemies had anything against Him, it was on account of some Jewish superstition that was beneath his notice. Satisfied, therefore, as to His innocence, Pilate brought Him out to the people and said:

"I find no cause in Him." The chief priests began to cry out, and to bring charge upon charge against Him. The Governor waited for His reply. But He answered nothing. Pilate was struck by this silence and looked well at the Man before him. Never had he had to do with so noble a prisoner; never had he seen such majesty and serenity, and such contempt of death. Wondering exceedingly he said again:

"I find no cause in this Man." But the priests only exclaimed more vehemently: "He stirreth up all the people, beginning from Galilee to this place." Pilate was naturally just. He saw through the accusations of the Jews. He knew that our Lord was innocent of all these crimes, and that He ought to be released at once. But Pilate was weak. He was afraid- that the Jews might report him to the cruel Emperor Tiberias, and that disgrace, or something worse, might befall him if he declared himself openly in favour of One who claimed to be a King. He tried therefore to strike a middle course, and began the wretched shuffling, which was the cause of so much shame and agony to our Lord and of such perplexity to himself.

The name Galilee brought up by the priests seemed to show a way out of the difficulty. Galilee belonged to Herod, who was in Jerusalem for the Pasch. Jesus of Nazareth as his subject should be tried by him. Greatly relieved at having thus shifted the responsibility on to another, Pilate sent our Lord to Herod, and congratulated himself on having brought to a successful conclusion an important and awkward case.

Herod was as much pleased to see our Lord as Pilate was to get rid of Him. For a long time he had wanted to get a sight of this extraordinary Man, and to see some of the marvels of which he had heard. His opportunity had come, for the Prisoner would surely be only too glad to gratify him and win his favour. On His appearance, therefore, before the courtiers assembled as for an entertainment, Herod treated Him with respect, showed an interest in His case, and asked Him many questions. But He who had answered Pilate would not deign to speak to this vicious prince, the murderer of St. John the Baptist, the man whom for his cunning He had called a " fox." Herod's conscience told him the reason of this silence, and, provoked at being thus put to shame before his court, he took his revenge by mocking his Prisoner. He had Him dressed up in a white garment as a fool, and in this guise sent Him back to Pilate.

Now, at last, the persistent efforts of the priests to dishonour Christ before the people were rewarded. The crowds that had flocked to Him in the Temple and poured out of Jerusalem six days ago to bring Him in triumph into the City, the crowds that He had loved and taught and healed, turned against Him. As He came out of Herod's palace in the fool's garment, He was received with hisses, jeers, and all the wonted insults of an Eastern mob.

It was an hour or two after Pilate had sent our Lord to Herod that He was told the soldiers were bringing Him back. The weak, cowardly judge was terribly perplexed. He knew what he ought to do, but he was afraid. He could not in justice condemn Jesus; he dared not release Him. A sudden thought struck him: the people might come to his help. There was a custom by which they were allowed at the time of the Pasch to have any prisoner they should choose released to them. They were beginning now to cry out for the grant of their annual privilege. Pilate saw his chance. He had then in prison a bandit and murderer called Barabbas. The people should choose between this man and Jesus—the people, not the envious priests, the people who would be terrified to see Barabbas let loose again. He mounted the platform in the Lithostrotos and seated himself in his chair of gold and ivory. His soldiers and servants took up their position behind him and the Prisoner was again summoned. All around was the multitude thronging every part of the enclosure.

"Whom will you that I release to you," cried the Governor, "Barabbas, or Jesus who is called Christ?" At this moment he turned aside to hear a message from his wife:

"Have thou nothing to do with that just Man, for I have suffered many things this day in a dream because of Him." His Apostles were hiding; His friends in the Sanhedrin, Nicodemus, and Joseph of Arimathea, were afraid to plead His cause; His priests were clamouring for His death. One alone in the holy City was found to speak for Him—the Gentile woman, who, from her splendid apartment, was looking down upon Him with reverence and with pity, Claudia Procula, Pilate's wife.

Her words agitated her husband greatly, and confirmed him in his resolution of saving this Just One from the fury of His enemies. But what might have been done with ease two hours ago was a difficult matter now. The chief priests were steadily making way, even the few minutes' interruption caused by Procula's message had not been lost by them; and when the Governor put his question a second time, the people, whom they had worked up to a state of frenzy, were ready with their reply.

"Whom will you that I release to you," he cried, "Barabbas, or Jesus who is called Christ?" A shout as of one voice went up: "Away with this Man and release unto us Barabbas." Astounded and disgusted, Pilate called out:

"What will you, then, that I do to the King of the Jews?" They cried out: "Crucify Him! Crucify Him!" "Why, what evil hath He done?" demanded the Governor. "I find no cause in Him. I will chastise Him, therefore, and let Him go." But again rose up that howl: "Crucify Him! Crucify Him!" Weary of the struggle, Pilate called for water and washed his hands before the people, saying: "I am innocent of the blood of this Just Man, look you to it." Oh, the awful shout that went up from the whole multitude there:

"His blood be upon us and upon our children!" In vain did the cowardly judge wash his hands, the guilt was upon his soul. On him depended the life or the death of Jesus Christ. Therefore will all Christians to the end of time say in their Creed: "suffered under Pontius Pilate."

The rage of the people was becoming more and more ungovernable; they were thirsting like wolves for the blood of this innocent Lamb, and now nothing less would satisfy them. Again Pilate yielded, and, to appease them and save Christ without harming himself, he had recourse to the shameful expedient of ordering Him to be scourged. Scourging was a punishment so cruel and so degrading that it was reserved for slaves. The poor victim often died under it, and, in itself, it was far worse than death. Trembling with fear, for He was truly man, our Lord was fastened by His wrists to a low pillar. Then the executioners, standing on a step to deal their blows more surely, struck Him unmercifully with their horrible iron-spiked lashes, which tore the flesh to the very bones. His sacred body was soon one wound; "from the sole of the foot to the top of the head there was no soundness therein, wounds and bruises and swelling sores," as the prophet had said.

And not a friendly face anywhere, none of all He had healed and comforted to help Him now! Gasping for breath, He sank at last to the ground, but only to be dragged off to a fresh torment. He had wanted, it was said, to be a King; well, the soldiers would have the coronation in their barrack room. They tore off His garments, which they had put on roughly after the scourging and which clung to His wounded body; threw over His shoulders an old, scarlet cloak, and put a reed into His hand for a sceptre. Then they plaited a crown of hard, sharp thorns, and beat it down with sticks upon His head and forehead, so that streams of blood trickled through His hair and ran down His face. Then they got into line and marched before Him, kneeling as they passed, and with shouts of laughter and cries of "Hail, King of the Jews!" came up to Him, some spitting on Him, some striking Him on the head, all trying who could ill treat Him most.

Our Lord was a king, and He felt, as only a king could feel, the shame as well as the pain He had to endure. But He sat there bearing all meekly as the prophet had foretold: "I have given my body to the strikers, I have not turned away my face from them that spit upon me." Accustomed as he was to cruel sights, Pilate was struck with horrror and compassion when our Lord appeared again before him. The face so beautiful an hour ago was quite disfigured, swollen, bruised, besmeared with blood. His limbs trembled, He could scarcely stand. The half closed eyes were dim with tears and blood. The scourging must have been horrible, thought the Governor, but at least it has saved His life; a sight so piteous would melt hearts of stone.

There was a balcony built over the archway that overlooked the thronged entrance to the Praetorium. Here, where He could be seen by all below, Pilate placed our Lord, still clothed with the old, red cloak, thrown over His bleeding shoulders, His eyes half blind with pain.

"Behold the Man!" he cried. "I bring Him forth to you that you may know I find no cause in Him."

"Crucify Him ! Crucify Him!" they shouted. "He ought to die because He made Himself the Son of God."

"Son of God!" Pilate was filled with a new and terrible fear. Innocent this Man certainly was. But what if He were something more, what if He were a God! Never, surely, had man borne himself like this Man, with such calm dignity, such invincible patience in the midst of torments and shame. He dared not leave this awful question unsolved. He must see Him again in private. "Whence art Thou?" he asked, when they were again alone. But Jesus gave him no answer. Pilate, offended, said to Him:

"Speakest Thou not to Me? Knowest Thou not that I have power to crucify Thee and I have power to release Thee?" Jesus answered:

"Thou shouldst not have any power against Me unless it were given thee from above." It was between ten and eleven o'clock when the poor, irresolute judge again appeared with his Prisoner in the Lithostrotos. He was greeted with the shout:

"If thou release this Man, thou art not Caesar's friend.""Behold your King," was his reply.

"Away with Him! away with Him!" they shouted.

"We have no king but Caesar." Pilate's courage gave way. He had to choose between Caesar and Christ, and to keep Caesar's favour "he released unto them him who for murder and sedition had been cast into prison, whom they had desired." says St. Luke, "but Jesus he delivered up to their will."

All over the City was heard the howl of triumph with which the sentence was received. No time was lost in carrying it out, lest Pilate should repent and recall it. The cross, already prepared, was brought out, and the title Pilate had ordered to be fixed to it: "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews."

The procession formed and set out in all haste. First came on horseback the centurion, whose duty it was to preside at the execution and to maintain order in the crowd; next a herald bearing the title of the cross and proclaiming the crimes of the condemned. Then two thieves to be crucified. Last of all, our Lord, weak and tottering, yet laden with His heavy cross. On each side of Him the soldiers who were to fasten Him to the cross and guard Him till death. Running on in front, shouting and laughing, children who had sung "Hosanna!" six days before. All around and behind, an immense multitude hooting and jeering, those nearest throwing mud and stones at Him after the fashion of an Eastern crowd.

What a spectacle was Jerusalem that Friday morning nineteen hundred years ago!—a mass of men, women, and children choking up every thoroughfare, pouring along under the arches that cross the narrow roadways, climbing and descending in endless procession the steep streets of the hill-built City; all going the same way, all talking excitedly, rejoicing that justice had at length overtaken "the seducer" and "blasphemer."' Roofs, windows, doorways, filled with eager sightseers; rabbis and priests hurrying about among the people, in a fever of anxiety lest anything should happen to prevent the execution.

The way to Calvary was long and painful, now up hill, now down, sometimes a series of steps. Our Lord struggled on slowly; three times His little remaining strength gave way, and, gasping for breath, He sank beneath His load. Fearing He would die before He could reach Calvary, the soldiers forced a countryman, Simon of Cyrene, to carry His cross. At a street corner was a little group waiting to see Him pass—His Blessed Mother with the Beloved Disciple, Magdalen, Mary of Cleophas, and Salome. The Mother's face would have moved a heart of stone; but hearts in Jerusalem were harder than stone that day, and there was no more pity for the Mother than for the Son. She saw the ladders, the ropes, the cross. And then, staggering along, she saw Him coming. Their eyes met, and He looked pityingly at her. They did not speak, but He strengthened her breaking heart, that she might be able to endure to the end. There were many hard things to bear on the road to Calvary, but to the tender Heart of Jesus the hardest of all was the sight of His Mother's face.

A little further on He stopped to speak to the weeping women of Jerusalem. All through His life of hardship and persecution women were faithful to Him and showed Him reverence. A woman's voice from the crowd had been raised to bless Him as He preached; women ministered to His wants, received Him into their houses when all other doors were closed against Him, lavished upon Him costly gifts which even His own disciples grudged Him. In His hour of need a woman's voice alone was raised in His defense. And now, heedless of the rough soldiers and the hooting rabble, a crowd of women pressed round Him and filled the air with their lamentations. What wonder that He could not leave them without a parting word! But it was a word of solemn warning, for He knew what was coming upon them and upon the little ones they carried in their arms.

"Daughters of Jerusalem," He said, " weep not for Me, but weep for yourselves and for your children."

About twelve o'clock Calvary was reached. It was a mound outside the walls, the place of public executions —a place of horrors. Our Lord was quite spent. The priests who crowded round Him could see He was dying.

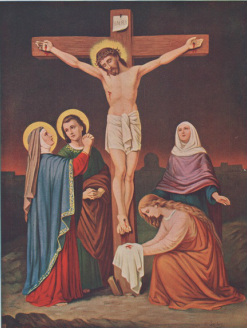

"Quick, quick," they cried, "or it will be too late!" And whilst the soldiers kept the ground clear, He was thrown down upon the cross and ordered to stretch out His arms. His terror was indescribable, for He was truly man. Yet He obeyed without a word. One strong blow, and a long nail was driven through the right hand into the wood. The left arm had to be drawn with ropes to the hole drilled for it in the cross. Then it too was nailed fast. They dragged the feet till the sinews broke and the bones were out of joint. The torture was beyond what we can even think. Yet it was not able to turn His thoughts from us and our needs. He must make haste to appease His Father'sanger, aroused by this awful crime, to pray for His executioners and for all who have crucified or will crucify Him again by sin.

"Father, forgive them" He said, "for they know not what they do" St. John, who was there, tells us that" when they had crucified Him, the soldiers took His garments and made four parts, to every soldier a part, and also His coat. Now, the coat was without seam, woven from the top throughout. They said then one to another:

"Let us not cut it, but let us cast lots for it whose it shall be, that the Scripture might be fulfilled, saying: "They have parted My garments among them, and upon My vesture they have cast lots." And the soldiers indeed did these things."

Meantime the thieves, shrieking and blaspheming, had been crucified, and the three crosses raised into position and firmly fixed with wedges driven in all round. Then at last the enemies of Jesus were satisfied. The priests came up and stood before His cross and cried:

"Yah ! Thou that destroyest the Temple of God and in three days dost rebuild it, save Thy ownself. If Thou be the Son of God, come down from the cross and we will believe." The people came and stared, blaspheming like their rulers. One of the thieves cried out:

"If Thou be Christ, save Thyself and us." But the other rebuked him and said:

"We, indeed, receive the due reward of our deeds, but this Man hath done no evil." And he said to Jesus: "Lord, remember me when Thou shalt come into Thy Kingdom." And Jesus said to him:

"Amen, I say to thee, this day thou shalt be with Me

in Paradise." Our Lord had always loved sinners. And now He gave these poor men grace to know that He who shared their disgrace and was put between them as the most guilty was the long-expected Messiah, the King of Heaven and earth. One of them, alas! only one, opened his heart to grace, was sorry for his sins, took his punishment humbly, and, for the simple remembrance which he asked, received the forgiveness of his sins and the promise of Heaven in the company of his Saviour before the sun had set.

Sinners first, sinners even before His Mother. But His next thought was for her. She was losing all in losing Him; He must provide her with a home. Brave and patient she was standing beside His cross, and, except for her companions and the centurion and his men, almost alone. A strange darkness creeping over the heavens had frightened away the crowds; there was room now by the cross; John had brought her up to it, and she had taken her stand there beside her Son to stay with Him until the end. His eyes were dimming fast. He could scarcely see. But He turned them painfully to her and then to John, and said to her:

"Woman, behold thy son." After that He said to John: " Behold thy Mother." And from that hour the disciple took her to his own. She was given to the Beloved Disciple, and in him to

all disciples. Mary, the Mother of God, became the Mother of us all that day. And now there was darkness over the whole earth, not that of a dark day, but the darkness of night. Our Lord had hung in silence a long time, when, suddenly, a loud cry broke from His lips:

"My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken Me?" How hard it is to understand that cry! We should have thought His Heavenly Father would have leaned in tenderest pity over that cruel cross and have filled with consolation the soul of His dying Son. It was to win back for His Father our perishing souls that He had come down from Heaven; all His life through He had sought, not His own glory but his Father's; He had done everything His Father asked of Him—why was He forsaken? Because He was being treated as a sinner. Sinners deserve to be forsaken by God in this world and in the next. He would take their place, and suffer this most dreadful pain and punishment in our stead, that we may know we are never, never forsaken by God in this life, no matter how lonely or how sinful we may be.

Of all the pains of crucifixion, the most terrible is thirst. It is so awful that the crucified seem to forget every other, and, as if there were nothing more to ask, beg only of the passers by a drink of water in their intolerable pain. It is loss of blood that brings this thirst. What must His thirst have been after the sweat of blood in the Garden, after the scourging, and now the draining of His sacred body on the cross? But it was not to get relief that Jesus cried:

"I thirst" but that David's prophecy of Him might be fulfilled: "In My thirst they gave Me vinegar to drink." On hearing His cry, a soldier ran, and filled a sponge with vinegar from a vessel that stood by, and, fixing it on a reed, put it to His mouth. And now at last, after three hours of agony, the end was come. When He had taken the vinegar Jesus said:

"It is finished." All He had come to do was done—the world redeemed; a perfect example set us in each stage of His blessed Life; every prophecy concerning Him accomplished; His Church founded, by which His followers in every age were to be taught what He had done for them, and how they must save their souls. He had spared Himself in nothing; He had sacrificed for our sakes, all He could give up—home, friends, reputation-- He had loved us to the end—all was finished. And again, crying with a loud Voice, He said:

"Father, into Thy hands I commend My spirit." The eyes closed; the head fell forward on the breast; the body sank low on the nails—He was dead. And the veil of the Temple that hid the Holy of Holies from the sight of men was rent from top to bottom. And the earth quaked, and the rocks were rent, and the graves were opened, and many of the bodies of the saints that had slept arose, and, coming out of the tombs after His Resurrection, came into the holy City and appeared to many. And the centurion and they that were with him watching Jesus, having seen the earthquake and the things that were done, were sore afraid, saying:

"Indeed this was the Son of God." And all the multitude of them that were come together to that sight and saw the things that were done returned striking their breasts. In vain did the priests try to quiet the people, Jerusalem was beside itself with terror; the rocking earth, the opening graves, the midnight darkness at midday all this spoke plainly for Him whose lifeless body hung upon the cross. There was no question of Feast or holiday. What they had done to Jesus of Nazareth was the one absorbing thought. All His goodness and gentleness and compassion, His teaching and His healing, came back to them; their cry of long ago:

"He hath done all things well;" their cry six days ago: "Hosanna to the Son of David!" their cry of this day: "Crucify Him! Crucify Him! His blood be upon us and upon our children!" They felt that an awful crime had been committed, and a dreadful sense of the anger of God enkindled against them weighed upon every heart.

Meantime evening was drawing on, and the Mother on Calvary had seen the last outrage to her Son. Soldiers had broken the legs of the thieves and taken the dead bodies away that they might not hang there to cast a gloom over the rejoicings of the morrow. When they saw that Jesus was already dead they did not break His legs, but one of them with a spear opened His side and so fulfilled the prophecy of Zacharias:

"They shall look on Him whom they pierced." She had no grave wherein to lay Him, but God, she knew, would provide. And, presently, there came up to the cross two men who up to this time had been disciples in secret for fear of the Jews. But now, when all Jerusalem was in fear, their hearts were filled with a new courage, and they had come to give honourable burial to their Master. Joseph of Arimathea had been boldly to Pilate and begged the body of Jesus, which he was going to lay in his own monument in the garden close by. Nicodemus came with him, and they brought fine linen and spices for the burial according to the custom of the Jews. Helped by their servants, they gently took down the sacred Body from the cross and laid it on the ground, the head on the Mother's knee.

The Soul was not there but in Limbo, rejoicing all the holy ones from Adam to the good thief, and turning that place of weary waiting into a very Heaven. The Divinity was with the Soul and with the lifeless Body too, and both were to be worshipped with the honour due to God. The preparations for burial had to be hastened, because of the Sabbath rest, which would begin when the first stars came out. With the help of Magdalen and John, Mary swathed Him in the long linen bands, and covered the white, disfigured face. Then they formed in sad procession and bore Him through the garden into the rocky tomb. There they left Him, and, rolling the great stone to the entrance, went their way.

As darkness fell for the second time that awful day, the disciples left their hiding places and crept back one by one to the Upper Chamber on Mount Sion, which now became their ordinary place of meeting. There they gathered round John to hear all that had befallen the Master since they had left Him in the Garden. They listened in trouble and in shame, poor Peter's tears running fast down his rugged face, all sorrowing over their cowardly desertion of their Master, all envying John who had stood by Him to the last. Then they talked of the past, of the happy days in Galilee, of their nights with Him on the mountain side, of His gentle, patient teaching, of His tenderness to them at the Supper in this very room. And now all was over, and had ended in this! There was nothing more to live for. They remembered how clearly He had foretold to them all that had come to pass—the betrayal, the scourging, the crucifixion; but not one of them called to mind that last word with which He always ended: "the third day He shall rise again."

Far into the night they talked; then, weary and comfortless, broke up the meeting and went back to their homes. On the festival day they were together again in the same place, going over all anew. Others came in, but there was no comfort from any. All was over, they said again and again to one another as they mourned and wept. His friends, then, were weighed down by hopeless sorrow. But what about His enemies? They were rejoicing surely? The priests had promised themselves a quiet evening after their anxious day. All had gone better than they had dared to hope. Through the cowardice of Pilate, insult and torment beyond what they could have desired had been heaped upon "the seducer," and now He was safely in His grave, and all was over. But was it? This, in their hour of triumph, was the question they kept asking themselves. The darkness, and the earthquake, and the rent veil in the Holy Place, were being taken as signs of His innocence and of the wrath of God upon His enemies; and not by the common people only but by men of note and their fellow Councillors in the Sanhedrim Word had been brought to them how the centurion and his soldiers had proclaimed the Crucified to be the Son of God, and how Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea had given Him honourable burial. Of course they themselves had no further fears. He was certainly dead, and His disciples were far too timid to give cause for alarm. And yet there was that word of His about rebuilding the Temple in three days. What if there should be anything in it! What if anything should happen on the third day! It would be well to guard against such a calamity. No precautions could be too great to prevent a reappearance which would at once mark all His words and works as divine and prove Him to be in very deed what He had given Himself out to be. They would make all safe by applying to Pilate for a guard until the third day.

It was the afternoon of the Sabbath when the Governor was told that a party of priests craved an audience. Tortured by his conscience, and terrified by all that had followed upon the Crucifixion, Pilate was in no mood to receive visitors, and least of all these hateful men who had forced on him the deed of yesterday. Very unwillingly he gave orders for their admission.

"Sir," they said, bowing low before him, "we have remembered that that seducer said while he was yet alive; "After three days I will rise again." Command, therefore, the sepulchre to be guarded until the third day, lest perhaps his disciples come and steal him away, and say to the people that he is risen from the dead, and the last error shall be worse than the first."

"You have a guard, go guard it as you know," was the curt reply. And they, delighted to have gained their point so easily, departed and made all secure by sealing the stone of the Sepulchre and setting four Roman soldiers to guard it.

A printable file of this chapter as well as a coloring picture can be found below.

|

| ||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed